This is the transcript of a podcast episode that you can listen to here.

Hey everyone.

Well, it’s certainly been a while since my last episode, so I hope you’ve all been doing well in my absence from your life (that doesn’t sound too grandiose now, does it?!). Today’s episode will cover two separate but related topics. The first topic is about the start of Men’s Health Week, which aligns with a book I recently read and want to review. And rather than discussing them separately, I thought I would cover both topics together.

But before we get into that, this is the usual appeal to let others know about my podcast. The only way any learning from this show gets spread to the masses is through your kind efforts of sharing and reviewing the podcast. So, at the end of this episode, if you liked what you heard, please do me a solid and spread the word. Thank you.

So, for those who are unaware, Men’s Health Month is observed every June, along with Pride Month (and probably some other important things that I am not currently aware of). This is the first of two months dedicated to considering men’s health needs across the year, as November (otherwise known as Movember) also focuses on men’s health. I won’t lie; it is sometimes confusing when looking these months up because both the June and November months can be equally referred to as Men’s Health Month and Men’s Mental Health Month, depending on which website you land on. However, there seems to be general agreement that Men’s Health Month in June (and in November, I guess) is an initiative to raise awareness about men’s health issues and promote the adoption of healthier lifestyles for men. It’s a dedicated time – according to menshealthmonth.org – for awareness, prevention, education, and family engagement, all aimed at the health and well-being of men and boys. Overall, this month is meant to serve as a reminder for men to take charge of their health, as they are often less likely than women to seek medical attention or report symptoms to a healthcare provider.

Now, I can’t quite tell, as there isn’t a very obvious outline of the difference between the two months online, but I think the reason that there are two Men’s Health Months in the year is because Movember started as an initiative in Australia and is the same month and International Men’s Day (November 19th, in case anyone didn’t know) and specifically focuses on growing a moustache as part of the campaign for awareness and fundraising (although in reality you can now do other things other than grow a moustache to raise money). Whereas Men’s Health Month in June seems to be built around International Men’s Health Week, which is celebrated in the week leading up to and including Father’s Day. So this year, in 2024, Men’s Health Week will be observed from Monday, June 10th to Sunday, June 16th. So it is not a coincidence that I have released this episode today.

According to Wikipedia, International Men’s Week started at the American Congress in 1994—so the concept is three decades old—but then reached an international level when representatives from six men’s health organisations around the world met at the World Congress in 2002. So, at an international level, it has been around for just over two decades.

In line with the aims of Men’s Health Month, Men’s Health Week also focuses on giving boys and men access to the information, services, and treatment they need to live healthier, longer, and more fulfilling lives. From what I can tell, there can be several themes for Men’s Health Week. For example, here in England, the Men’s Health Forum is promoting that men talk more about prostate cancer (this seems to have followed King Charles discussing his own Cancer scare earlier this year) Meanwhile, the theme in Ireland for Men’s Health Week is ‘Know Your Numbers’, which encourages men to be aware of key health numbers critical for our well-being. And again, in America, the Men’s Health Network notes that this year’s theme for Men’s Health Week is to “teach men and boys how to fish (for health)” with the goal of “build[ing] the knowledge of men and boys to impact their lifestyle for actionable, healthier choices that influence decisions, lifelong.” So, the themes can be quite broad; but overall, the idea behind both Men’s Health Month and Men’s Health Week is to heighten awareness of preventable health problems for males of all ages, support men and boys in engaging in healthier lifestyle choices and encourage the early detection and treatment of health difficulties.

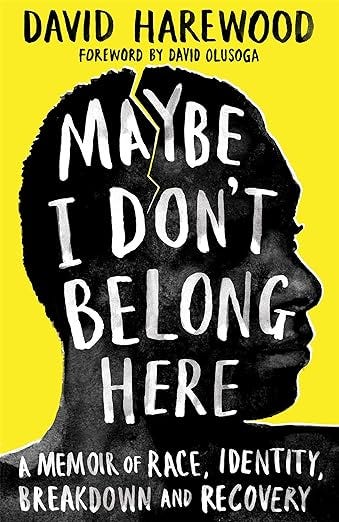

As I mentioned earlier, June and November are also sometimes called Men’s Mental Health Month. Why it gets confused or called something different doesn’t matter because I think—along with all aspects of health—it is important to discuss and demystify difficulties with mental health. And in the spirit of that, and because one of the things I want to start doing on this podcast is book reviews, I thought it might make sense to have a chat about a book I recently read that focuses on a man’s experiences of mental illness: “Maybe I Don’t Belong Here” written by acclaimed actor David Harewood. I mostly know David Harewood from the first two seasons of Homeland, but he is also a familiar face in British film and television. “Maybe I Don’t Belong Here” is a memoir in which Harewood shares his experiences of growing up both Black and British, how this impacted the development of his mental illness, and how he came out the other side of his difficulties to then go on to become a successful Hollywood actor.

I thoroughly enjoyed this book for three reasons.

Firstly, the book provides an informative and insightful look at the link between experiences of racism and the development of mental illness. It offers a firsthand account of how social inequality can affect someone’s sense of self and contribute to significant mental health issues. David Harewood touches on some statistics about this in his book, which is supported by data from the Mind charity website. For example, in the UK, people from black communities are more likely to experience a common mental health problem in a given week (23% Black of Black British compared to 17% White British). Additionally, people from Black and Black British communities are four times more likely to be detained in a psychiatric hospital under the Mental Health Act. People from the black community are also more likely to be detained more than once, which is something that happened to David Harewood. Additionally, this demographic is ten times more likely to be on a Community Treatment Order, which is another part of the Mental Health Act that allows a person with mental health issues to receive care and treatment in the community.

I have heard these statistics before, and have created content around them on my Instagram page. However, listening to a book written by a man with firsthand experience of living these statistics really brought those facts to life. Particularly how David Harewood describes his experiences of racism and his confusion about his racial identity and position as a Black man within English society. The book’s title, “Maybe I Don't Belong Here,” reflects David Harewood’s uncertainty of whether he belonged anywhere as he was growing up because of the colour of his skin.

The second thing I really appreciated about this book is that it discusses psychosis, which is what David Harewood was diagnosed with in his early 20s. In the media, there’s usually only a focus on depression and anxiety. This makes sense considering that psychotic disorders occur in fewer than 1 in 100 people in a year, while in the UK, depression can affect 3 in 100 people, and generalised anxiety disorder can affect 6 in 100 people. Additionally, mixed anxiety and depression afflictions affect 8 in 100 people. However, something that is particularly noteworthy given David Harewood’s race and gender, is that black men are 10 times more likely than white men to experience symptoms of psychosis.

While the conversation around depression and anxiety has become more prevalent, mental illnesses such as psychosis – which is a form of mental illness characterised by hallucinations and delusions – still face significant social stigma and misunderstandings. As an example, David Harewood, in his book, discusses how it took him producing a documentary for the BBC called “Psychosis and Me” to fully understand psychosis, despite being diagnosed with it at the age of 23 and being in his late 50s when writing the book. His openness about his experiences with psychosis in a widely accessible and personal manner can only help to increase understanding and reduce the stigma around this kind of experience.

And the final thing that I really enjoyed about this book is that – as well as demystifying and talking quite openly about his experiences of psychosis – David Harewood also talks about his recovery. I think possibly one of the reasons that psychosis is not talked about much – or at least one of the things that adds to its stigmatisation and, therefore, reluctance to openly discuss it – is because it is thought to be a lifelong disability. Whilst this might be true for some people, according to the Yale School of Medicine, 25% of people who develop psychosis will never have another episode, while another 50% may have more than one episode, which is what happened to David Harewood. Despite that, they will be able to live normal lives. The website also goes on to say that psychosis is treatable and that it is widely accepted that the earlier someone gets help, the better the outcome.

Despite this being a book review, I won’t say much more about his recovery or anything else within the book because I think that would be giving too much away. However, I think it’s fair to say that the three reasons I enjoyed this book potentially overlap with some of the themes mentioned for Men’s Health Week. For example, the book relates to knowing the numbers in relation to the impact of racism on people from marginalised groups and the likelihood of developing mental illness because of this. Similarly, the information in this book goes a long way in helping people understand how somebody develops a mental illness. That being, that it is often quite a slow process that develops over time and is not something that just happens in a vacuum without any contributing factors. The book is also an education in the process of recovery, what that looks like, and what someone can do beyond their illness despite having had an experience as challenging and difficult as psychosis.

As a final note, I listened to “I Don't Belong Here” on audiobook. It was quite poignant and inspiring to hear David Harewood tell his story in his own words. I found it more profound to listen to him tell his story himself. So that is one more thing I liked about the book.

For these reasons, I strongly recommend reading this book, especially if you are a man and if you are white. It provides an insightful and in-depth look at how people experience the world and perceive their place within it and how that can impact their mental health, to the point where they can develop a mental health disorder. As a psychologist, I found it a truly remarkable book to listen to, and I think it is so important to be aware of and read. So, go do it.

And there we go…

Thank you for taking the time to listen to this episode. As I said earlier, if you enjoyed it, please share it with your family, friends, and colleagues. Also, if you would be so kind, please leave a rating. That would be greatly appreciated.

As always, until next time, I hope you have a fucking great day. Or not. No pressure.

Goodbye for now.